Why Sealant Failure Is One of the Most Overlooked Sources of Moisture Intrusion

Sealant failures are rarely dramatic at first. Small separations, hairline cracks, or hardened joints often go unnoticed until interior damage appears.

In Chicago’s climate, those minor openings are exposed to repeated freeze–thaw cycles, wind-driven rain, and seasonal movement. Over time, moisture finds its way behind masonry, accelerating deterioration well beyond the joint itself.

Sealant is not decorative. It is a critical water-management component of the building envelope.

What Sealant Does, and Why It Fails Over Time

Sealant (often referred to as caulking) is designed to absorb movement between dissimilar materials while remaining watertight. It is commonly installed at transitions such as masonry-to-metal, masonry-to-glass, and masonry-to-concrete.

Because these areas experience constant movement, sealant plays a critical role in preserving the overall performance of the building envelope. Guidance from the Concrete Masonry & Hardscapes Association (CMHA) emphasizes that joint sealants are especially important at control joints, window and door perimeters, and transitions between different building components. These joints are intended to accommodate drying shrinkage, thermal movement, and differential movement while maintaining weather-tightness.

Failure typically occurs due to:

- Natural aging and loss of elasticity

- Improper joint sizing or backing material

- Incorrect sealant selection for the exposure condition

- UV degradation on south- and west-facing elevations

- Movement caused by thermal expansion and structural deflection

Once sealant loses adhesion or flexibility, it stops shedding water as designed.

Common Locations Where Failed Sealant Allows Water Entry

Sealant failures rarely occur in isolation. They tend to appear repeatedly in predictable areas across a façade.

Typical moisture entry points include:

- Window and curtain wall perimeters

- Expansion and control joints

- Shelf angles and lintel interfaces

- Coping caps and parapet transitions

- Balcony edges and guardrail penetrations

In many Chicago buildings, especially mid-century and historic masonry construction, original sealant systems were never intended to perform indefinitely.

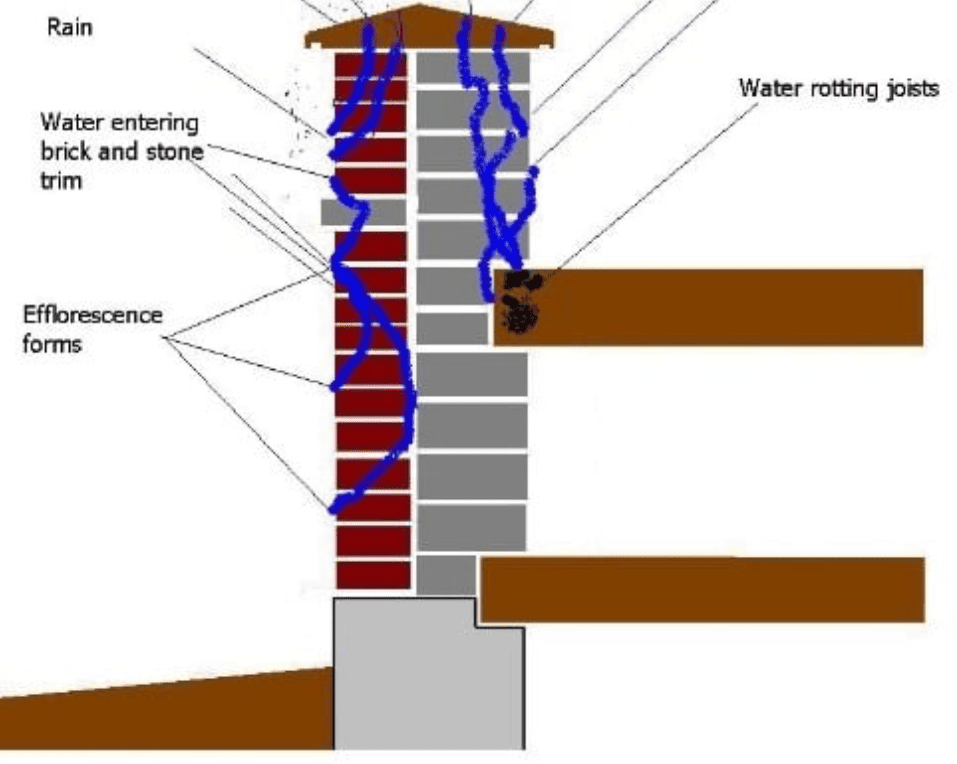

How Moisture Travels After It Gets Past the Sealant

Water rarely stops at the point of entry.

Research published through the Penn State College of Engineering has shown that when masonry movement joints are unable to accommodate expected thermal and moisture-related movement, stresses are redistributed into adjacent materials rather than being relieved at the joint. This condition can contribute to joint separation, localized cracking, and displacement near openings, lintels, and parapets, creating additional pathways for water entry.

Once moisture bypasses a failed joint, it can:

- Migrate laterally within the wall cavity

- Saturate backup masonry or concrete

- Accelerate corrosion of lintels and shelf angles

- Freeze and expand, causing brick cracking or displacement

- Appear as interior staining far from the original failure

This is why visible interior leaks often mislead teams into treating symptoms instead of the source. The diagram below illustrates how water can migrate within a masonry wall assembly after entering through a failed joint, often traveling away from the original point of entry before becoming visible.

Chicago-Specific Factors That Accelerate Sealant Failure

Chicago buildings face exposure conditions that shorten sealant service life compared to milder climates.

Key contributors include:

- Freeze–thaw cycling: Moisture trapped at joints expands repeatedly in winter

- Wind-driven rain: Especially along lakefront and high-rise corridors

- Thermal movement: Large daily and seasonal temperature swings

- Historic façades: Older masonry often lacks modern water management detailing

These factors make proactive sealant evaluation especially important in the Chicago region.

Early Warning Signs Property Management Teams Should Not Ignore

Sealant rarely fails overnight. Most problems provide visible clues well before major damage occurs.

Guidance referenced by the U.S. Environmental Protection Agency on moisture intrusion emphasizes that sealants have a limited service life and should be inspected regularly as part of a broader building envelope evaluation. Early visual indicators, such as deteriorated sealant, staining, or residue, often signal loss of elasticity or adhesion that can allow water to bypass the exterior envelope.

Watch for:

- Cracked, brittle, or shrinking sealant

- Gaps between sealant and masonry edges

- Recurrent interior staining near windows or slab edges

- Rust staining below lintels or shelf angles

- Efflorescence forming near joints

Addressing these indicators early can prevent more invasive masonry restoration later.

When Sealant Repairs Alone Are (and Aren’t) Enough

Not every moisture issue requires a full façade restoration. In many cases, targeted caulking and sealant repairs are sufficient.

However, sealant repairs should be paired with further investigation when:

- Moisture intrusion has been ongoing

- Corrosion staining is present

- Masonry cracking accompanies joint failure

- Prior sealant replacements have failed prematurely

In these cases, coordinated repairs may include tuckpointing, lintel and shelf flashing repairs, or localized concrete façade repair.

Why Professional Sealant Assessment Matters

Sealant performance depends heavily on preparation, joint geometry, and material compatibility. Improper removal or incorrect product selection often leads to early failure, even with new installation.

As part of our commitment to best practices in masonry restoration, RestoreWorks regularly collaborates with industry organizations like the International Masonry Institute (IMI). Earlier this year, we hosted a hands-on masonry restoration workshop with IMI at their Addison, Illinois facility, where one of the most in-depth stations focused on sealants. The session highlighted how joint design, surface preparation, material compatibility, and field testing directly influence sealant performance and long-term building envelope durability.

Experienced caulking contractors evaluate:

- Joint width-to-depth ratios

- Substrate condition and movement characteristics

- Compatibility with adjacent masonry and metals

- Exposure severity by elevation and orientation

On complex façades, mock-ups are often recommended to confirm appearance, adhesion, and performance before full installation.

How Sealant Maintenance Fits Into a Broader Masonry Strategy

Sealant work should not be viewed as a standalone repair. It is most effective when integrated into a broader building envelope maintenance plan.

A coordinated approach helps teams:

- Extend the service life of masonry systems

- Reduce emergency leak responses

- Plan repairs around optimal weather windows

- Control long-term capital costs

BC Housing Research Centre guidance reinforces this approach, emphasizing that sealants require regular inspection and proactive maintenance because they typically deteriorate faster than the masonry systems they protect. Their research outlines a practical maintenance cycle, being inspection, cleaning, repair, and replacement, to prevent localized sealant failures from escalating into larger envelope issues.

In Chicago, sealant inspections are often most effective when scheduled ahead of spring thaw or before winter conditions return.

Frequently Asked Questions About Sealant Failure

How does failed sealant cause water leaks inside buildings?

Failed sealant creates gaps that allow rainwater to bypass the exterior façade. Once inside the wall assembly, moisture can travel horizontally or vertically before appearing indoors, often far from the original joint failure.

How often should sealant be inspected on commercial buildings?

Most commercial buildings should have sealant visually inspected every 3–5 years, with more frequent reviews for high-exposure elevations, lakefront properties, or buildings over 20 years old.

Can sealant failure cause structural damage?

Indirectly, yes. Chronic moisture intrusion can corrode steel lintels and shelf angles, weaken masonry, and contribute to freeze–thaw damage, which may eventually require structural masonry repairs.

Is caulking the same as waterproofing?

No. Sealant manages water at joints and transitions. Waterproofing systems address larger assemblies or below-grade conditions. Sealant is one component of a complete moisture-control strategy.

Have more questions about sealant failure? Contact RestoreWorks today.